A human chain that stretches back into history

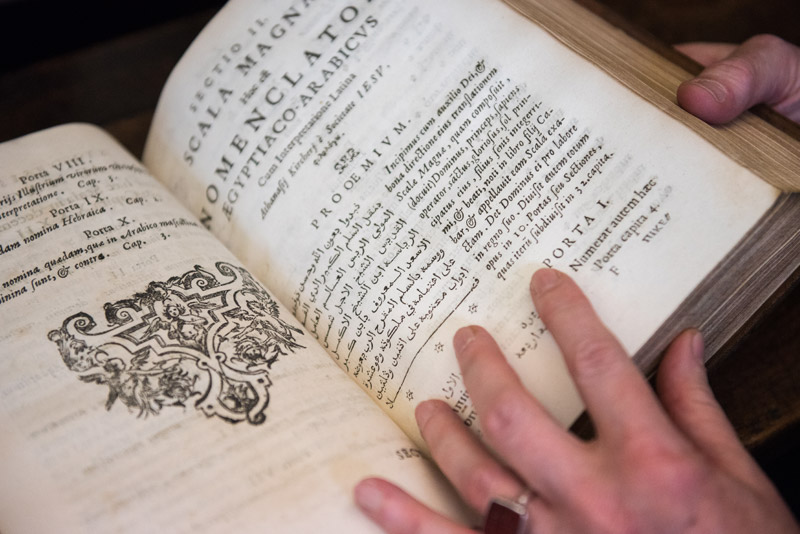

The study of Arabic language and literature at Oxford is a tradition that stretches back centuries. As Professor Julia Bray explains, its future has now been secured thanks to a generous donation.

It was a teenage encounter with a book with an exquisite cover that first drew Professor Julia Bray to Arabic literature. ‘Initially, I wasn’t looking for the demanding side of literature, I was looking at the sheer pleasure and the enchantment,’ she explains. ‘It’s wonderful to have that to fall back on, but of course there are other things as well.’

Forty years on, and Julia Bray now occupies one of the oldest and most prestigious chairs at the University of Oxford – the Abdulaziz Saud AlBabtain Laudian Professorship of Arabic. Her time is divided between teaching students at the Faculty of Oriental Studies, and pursuing her own research on medieval Arabic writing, chiefly its social uses and cultural meanings.

‘Literature is central to cultural memory and cultural consciousness, and therefore to the future,’ says Professor Bray. ‘It is what you feel you are now and where you feel you come from, that gives you a sense of what you could be.’ She believes classical literature to be an integral part of historical understanding, explaining that: ‘It says profound things about what people have felt and what they have aspired to. In every culture, classical literature is not a source of looking at the past in a glass case, but of thinking: what can I take from this to reconstruct myself?’

For undergraduate students reading Arabic at Oxford, the study of classical Arabic literature is compulsory – a requirement not always made at other universities. ‘It’s a small part of the syllabus here, but it’s an important part,’ notes Professor Bray. It is only by exposing students to a breadth of literature that, in her eyes, the history and culture of Arabs and Islam can truly be understood.

In 2016, a generous benefaction from Mr Abdulaziz Saud Al Babtain re-endowed the Laudian Chair in Arabic, securing the study of this important field at Oxford for future generations. ‘The fact that this chair has been safeguarded after I retire means that classical Arabic literature is going to have at least one bastion in the UK,’ says Professor Bray.

‘Without the endowment,’ she continues, ‘there wouldn’t have been the incentive to build the subject, as we are doing – it would all be too uncertain.’ At Oxford, classical Arabic literature is a one post-subject, with no other provision for its teaching. If a post is suspended, it can take a gap of just one or two years for a course to become impossible to teach.

Professor Bray believes the on-going development of Arabic literature options for taught graduate degrees to be particularly important, given the number of students coming on to Oxford with no prior experience of studying it. ‘This is their only chance to do it,’ she stresses. ‘It’s important to catch people who have an interest, and give them something to hang it on to.’

To me personally, this support means that the subject has a future.Professor Julia Bray

For Professor Bray, knowing that the subject has a future at Oxford has translated into greater ‘energy, as well as optimism’ for classical Arabic literature as a field, and she feels invigorated to find new ways of sharing her work beyond the bounds of the faculty. ‘It’s very enriching to be able to engage with the public. It’s an enjoyable process that can really change the way you think,’ she adds.

So far, this has involved collaborations with the Ashmolean Museum, and with the Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) – the latter resulting in a programme of poetry translation and storytelling outreach steered by novelist and cultural historian Dame Marina Warner. Professor Bray also has a long-term commitment to the Library of Arabic Literature, which brings editions and translations of significant 7th to 19th-century works to a wider public.

In all, Professor Bray’s eagerness to share her passion for classical Arabic literature is unwavering. ‘I find the literature very moving and it teaches me things,’ she says. ‘I think that we all need as much literary experience of every kind as we can get – it is the most radical and fundamental of educations.’