Prostate cancer has become the most common cancer in men in the UK. One in eight men will develop the condition at some point in their lives, with more than 47,000 new cases being diagnosed every year.

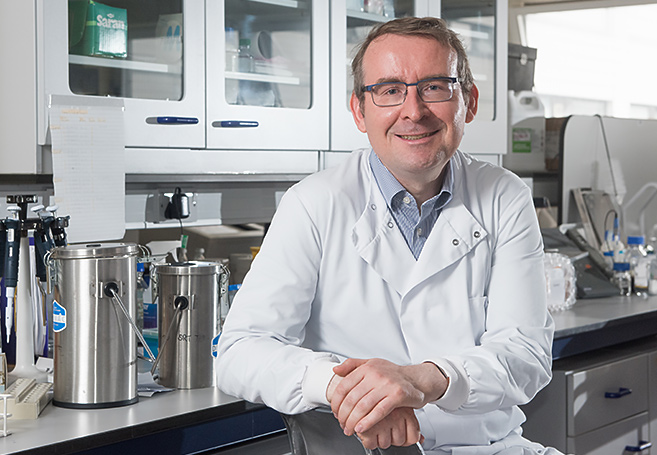

Professor Ian Mills first began researching prostate cancer in 2003. 'I'm a molecular biologist, so my entry point to the disease was a protein called the androgen receptor,' explains the John Black Associate Professor of Prostate Cancer. Androgen receptors work by binding to testosterone and steroid hormones, which are both regulators of prostate development and prostate progression in men.

In the years that followed, the genomics revolution has made it possible for researchers to map this process in unprecedented detail. The findings have had a significant impact upon the development of targeted hormone treatments, and much work is now being undertaken to increase their efficacy – often by combining clinically proven drugs with other forms of treatment, such as radiation or immunotherapy.

'What you're actually trying to target for curative therapy is a disease that's constantly evolving and changing,' says Professor Mills. 'It consists of millions of cancer cells, each with their own repertoire of defects and dependencies, so it's actually very challenging to think of curing it simply by zeroing in on a single protein. In order to fully capture and respond to its diversity, in the end you need a response biology that's equally adaptive, and that's the immune system.'

Professor Mills' research focuses on using targeted drugs to modify the inflammatory and immune response of the patient to the cancer, so that it 'can be effectively cleared from the body and cured'. He does this by developing preclinical models that, in turn, enable a better understanding of the way in which these drugs apply to cancer cells, and how they interplay with a functioning immune system.

If you're in a place where there are personalities that want to reach out to each other, work together and take risks with their research, philanthropic funding can be very powerful indeed.Professor Ian Mills

It's a lengthy process that involves editing the genome of cancerous cells to lock in or lock out particular genetic factors. The cells are then treated, either with radiation or targeted drugs, their DNA extracted and sequenced, and the results analysed. 'We're looking at the signals within those tumours and evaluating how they've changed in response to the edits that we've made,' explains Professor Mills. 'I'll then collaborate with clinicians and immunologists to try to think about how to apply these findings.'

Professor Mills is currently in the process of developing models of the disease that can be used by a number of different groups at the University, including teams based within his own department, the Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, as well as further afield. At the Big Data Institute, for example, work is being undertaken to predict genetic drivers of the disease, based entirely on the computational analysis of cancer sequencing data. 'There's the potential to collaborate with this group to do some functional biology on some of the targets they identify,' notes Professor Mills.

But although model development is key to better understanding the biology of prostate cancer, finding competitive research funding for this type of work can often be challenging. 'Many funders don't see their role as improving the context in which a disease can be better understood,' says Professor Mills. 'They want to know that the research they're supporting is going to have a direct treatment impact or an impact on cancer detection. Model development won't do that, but it will create the context in which it can happen.'

This is just one of the many reasons why donor support has proven invaluable to Professor Mills' work at Oxford. As he explains: 'Not only does philanthropy give me the opportunity to catalyse collaborations, but it also allows me to take leads, targets and candidate biomarkers that we've discovered and conduct more experiments. I don't have to slow down the pace of my work by filing grant applications. I can just keep pushing until the data shows us what's going to work.'

Professor Mills' post has been generously supported by the John Black Charitable Foundation.