Advancing research to prevent stroke and dementia

Researchers at the Wolfson Centre for Prevention of Stroke and Dementia are pooling their resources and expertise to combat these devastating disorders.

The statistics on stroke and dementia make for sobering reading: in the UK alone 100,000 people have a stroke each year, there are 1.3 million stroke survivors and an estimated 850,000 people are living with dementia. As the two most common disabling neurological disorders, they share similar risk factors and frequently co-exist, each increasing the risk of the other – having a stroke brings forward the onset of dementia by about ten years.

Professor Peter Rothwell, Action Research Professor of Neurology in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, is the Founding Director of the Wolfson Centre for Prevention of Stroke and Dementia based in a purpose-built facility at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford. The centre officially opened in March 2020 – thanks in large part to grants of £4 million from the Wolfson Foundation and £3.5 million from the Wellcome Trust. It builds on the achievements of the Stroke Prevention Research Unit, which Professor Rothwell set up in 2000, and which was awarded a Queen’s Anniversary Prize in 2014 in recognition of the impact of its research in improving patient care.

The new centre can accommodate up to 70 researchers with expertise in everything from epidemiology to genetics, and Professor Rothwell believes the very existence of a dedicated research centre is a big step forward for the field in the UK, particularly in terms of how stroke is perceived by young potential future researchers. ‘Stroke was traditionally rather neglected both by clinicians and researchers,’ he says. ‘Clinicians had an almost nihilistic attitude to it, partly because of a lack of effective treatments until recently, and partly because doctors tend to be more interested in rarities and stroke is anything but. Having a dedicated research centre in Oxford helps to raise the profile of stroke and vascular dementia.’

‘I think stroke is probably 90% preventable with the drugs and the other treatments we've got already. We just need to work out how best to use them and which patients are going to benefit most.’

The timing is also good because of recent advances in the treatment of stroke, which have necessitated more urgent and detailed investigation of patients in routine clinical practice. However, there is still a great deal of work to do – partly a legacy of a longstanding lack of research funding for stroke. Professor Rothwell cites the enormous disparity between the amount of funding for cancer and heart disease versus stroke – a reasonable comparison, he believes, because the cost to society of those three is about the same: equally common, equally expensive. ‘Around the year 2000, for example, there was about £400 million a year spent by UK cancer charities on cancer research and about £1.5 million spent by stroke charities on stroke research,’ says Professor Rothwell. This disparity in charitable funding meant there were far fewer funded stroke researchers who could then submit bids to governmental funders, and so these other potential funders also neglected stroke.

‘The situation is a little better now, but these disparities cast a long shadow,’ says Professor Rothwell. ‘A lot of very simple research could have been done 50 years ago and still needs to be done, such as on the mechanism whereby high blood pressure causes stroke – the most important risk factor – about which we know very little. Long-term average blood pressure is important, but short-term peaks can also trigger a stroke. The highest peaks tend to occur in the morning, when the risk of stroke is also highest, and so we are working on simple ways to monitor and stabilise blood pressure and on trials to determine which types of blood pressure-lowering tablets are best taken in the morning or the evening. And there's also so much that we don't know about the effects of other commonly used drugs. Patients with stroke, for example, are usually prescribed life-long aspirin to reduce the risk of recurrent strokes. We have shown that aspirin is highly effective initially, but we know very little about longer-term effects on risk of dementia and other complications of stroke.’

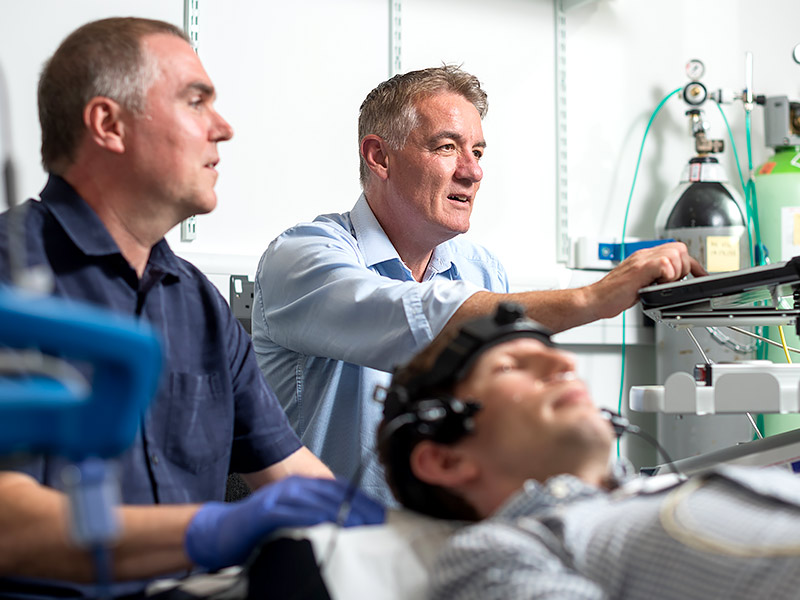

Professor Peter Rothwell observes in a clinical setting. Photo by John Cairns

Professor Peter Rothwell observes in a clinical setting. Photo by John Cairns

It is, of course, prevention that is at the heart of the research at the centre: developing better tools to identify which people are at risk of stroke or dementia and the interventions that are most likely to prevent that. For this reason, research at the centre is firmly embedded in clinical practice. Professor Rothwell explains: ‘In one of the studies we run, called the Oxford Vascular Study, we try to recruit and follow up all patients with stroke and other acute vascular events in a population of just under 100,000 people registered with nine general practices in Oxfordshire. To facilitate this, we provide a dedicated clinical service for GPs to refer to, we see patients urgently, and we do all of the investigations that they’d normally get on the NHS, but we also provide additional investigations that allow us to treat patients more effectively as well as to collect data for our research.’

The economic argument for the centre is strong and is best exemplified by the EXPRESS Study, a previous project that showed how effective urgent investigation and treatment were in preventing major stroke in patients who had transient stroke-like ‘warning’ symptoms. ‘We managed to reduce the early risk of major stroke by 80% – just by seeing patients urgently and using existing treatments more effectively,’ says Professor Rothwell. ‘Most medical interventions cost money, but this one actually saved money, because the strokes that were prevented would have been more expensive to care for than the service was to provide.’ The service was subsequently adopted across the UK as part of the National Stroke Strategy and is estimated to prevent about 10,000 strokes per year and to save the NHS around £200 million per annum.

Clinically embedded research is clearly key to this kind of success and numerous examples of this approach are in evidence at the centre, including Professor Sarah Pendlebury’s research on confusion and dementia in acute medical admissions under her clinical care. Home blood pressure monitoring is another example, where people with a recent stroke measure their blood pressure daily at home and the results are beamed back to central computers at the centre. Researchers monitor the readings in real time and quickly get patients on to the right doses and combinations of tablets to control their blood pressure. Patients feel empowered by being so closely involved in sorting out their risk factors and the researchers can assess whether this approach reduces the risk of further strokes.

‘We are the only purpose-built centre in the world dedicated to doing the clinical research needed to prevent stroke and vascular dementia.’

Clinical research into stroke and dementia requires very similar resources, relying on, for example, high quality brain imaging and detailed vascular physiology studies, and on multidisciplinary working. ‘For a lot of our studies, we recruit a cohort of patients with a particular condition and do the detailed clinical assessments and investigations (‘phenotyping’) necessary to allow collaborators to relate what they find in analyses of the patients’ blood or DNA as precisely as possible to the clinical condition.’

Oxford is an exceptional location for the Centre for Prevention of Stroke and Dementia due to its clinical links, its brain banks, its unique patient cohorts, and a critical mass of collaborative researchers. ‘The new building has allowed us to bring together about a quarter of all clinical stroke researchers in the UK under the one roof,’ says Professor Rothwell. ‘The centre also provides the space needed for our younger researchers to be able to build their own teams and to develop the new ideas that will ensure that we continue to make a difference.’

Support clinical neuroscience research at Oxford